PD Dr. habil. Wiebke Loosen

New players, new relationships - journalism and (its) audience

Introduction - or: "Who's afraid of the audience? Nobody! What if they come?

The internet and social media are changing the relationship between journalism and the audience: new forms of audience participation and users' changing demands for inclusion are leading to shifts between the traditional sender and receiver roles between professional and non-professional statement creation. What sounds comparatively sober in this form has been causing considerable organisational changes in editorial offices in practical journalism for several years, but also uncertainty, as journalists and users still find themselves in unfamiliar territory in social media.

I would like to start with a few highlights from the relevant literature on this topic, which can be used to illustrate the path that the relationship between journalism and the audience has travelled and is still travelling - and how research is observing this. At the end of the 1960s, Glotz/Langenbucher (1993, first published in 1969) spoke of the "disregarded reader"; this was, if you like, the "battle cry" of the 1970s, intended to make it clear that journalism paid too little attention to the needs and expectations of its audience. It was linked to the demand that journalists should give up their ingroup orientation, i.e. their focus on their own colleagues and their ideas of good journalism, in favour of a stronger focus on the needs of their audience.

40 years later, Meyen/Riesmeier (2009) then diagnosed a "dictatorship of the audience" - derived from numerous interviews with journalists. In a critical essay, the journalist Arno Frank (2013) speaks of the audience as a "mob with an opinion". He makes the interesting observation that much of the excitement on the internet and the lack of quality discourse is also due to the fact that many people are no longer aware of what subscribers to a particular newspaper know, namely "that they are more likely to read about certain topics in the FAZ than in the taz (and vice versa)" (ibid.: 20). The unbundling of media offerings, as a result of the dissemination of news via social media, may therefore also mean that we no longer have a proper idea of journalistic offerings, of the orientation of an editorial office.

In 2013, Pablo J. Boczkowski and Eugenia Mitchelstein (2013) presented the study The News Gap, which addresses the classic question of the connection between journalistic relevance criteria and audience preferences under the changed conditions of the internet. Their question: What are the top articles on the websites of American daily newspapers and what are the most clicked, shared and commented articles? They found a fairly large difference between the information preferences of journalists and their audience. However, this difference shrinks in politically active times, such as upcoming elections, because then there is also a greater need for information on the part of the audience. The size of the news gap between journalists and the public therefore depends heavily on the respective news situation and is not static. In addition, many journalists consider it a professional obligation to present their audience with socially relevant topics for which they assume there is less public interest: They therefore factor in a news gap from the outset.

For communication science, the topic of journalism and audience is also linked to the fact that we can observe a separation of the discipline within the discipline, so to speak: That is, journalism researchers are primarily concerned with the production side of journalism and its actors, while reception researchers are concerned with the audience side and media use. My colleague Marco Dohle and I took this as an opportunity to publish an anthology entitled Journalism and (its) Audience (2014). It attempts to overcome this separation to some extent and, to this end, looks at the interfaces between journalism research and reception research. One of our considerations was: If journalists are increasingly forced to think more and differently about their audience, then journalism, audience and reception research should also examine which findings, approaches and theories can be learnt from each other.

Finally, a study conducted by journalist Fritz Wolf for the Otto Brenner Foundation is even more topical: We are the audience (2015). The title of this study already indicates the escalation of the debate, as this publication deals with the "loss of authority of the media" and a "compulsion for dialogue", which the author identifies.

However, the changing relationship between journalism and (its) audience is not just a topic for journalism observers, but above all for journalism itself. In 2014, for example, the Swiss newspaper TagesWoche took the growing mistrust of the media as an opportunity to ask its readers for their views on "5 theses on mistrust of the media" - and came to the following conclusion based on the answers received: "The audience knows more than we do". And this is just one example - many other editorial teams have taken up the topic in a similar way.

Beyond this example from traditional, established journalism, we are also increasingly seeing the emergence of so-called journalistic start-ups - they often start with a different conceptual relationship to their audience. Last year, for example, Krautreporter was founded with funds from crowdfunding. Now, after a year, Krautreporter is to be transformed into a co-operative. Another example is the new service piqd, which offers expert curation of articles published elsewhere. Here, for example, the term "members" is used instead of "audience":

"We want to contribute to an informed public online. piqd is the counter-design to the reach-optimised algorithms of social networks. What is relevant is determined exclusively by our curators and members. We see ourselves as a kind of programme newspaper for the good web."

Incidentally, the aim is to ensure commentary culture "at the highest level" by only granting commentary rights to paying members. However, the membership fee of three euros per month is less about the money and more about "keeping trolls away" (ibid.). In other words, you don't pay for content, but for a membership status that allows you to comment.

Journalism and (its) audience: Illustrative findings from empirical research

The developments outlined up to this point should be viewed against the background that journalism and the audience have traditionally had a complicated, almost paradoxical relationship. On the one hand, it is undisputed that journalism needs an audience, because without an audience that accepts journalistic communication offers, there would be no journalism. On the other hand, however, the audience plays a rather subordinate role in the daily editorial routine. At the end of the 1990s, it was still assumed that the image of the audience of journalists under the conditions of mass communication was "by necessity largely independent of direct experiences and interactions" (Scholl/Weischenberg 1998: 125, footnote 22, italics in original). These communication conditions are based on the classical distinction between individual and mass communication, between communicator and recipient and between the production and reception of statements. However, this characterises conditions that only apply to social media forms of public communication (on the Internet) to a limited extent. Forms of audience participation, such as those that have become possible in social media like Facebook and Twitter as well as in comment sections of journalistic online media, have become important new sources that also characterise the image of the audience on the part of journalism and significantly expand the forms of interaction between the two groups (Loosen 2013).

These considerations were at the beginning of the research project funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) entitled Die (Wieder-)Entdeckung des Publikums. Journalism under the Conditions of Web 2.0, which I led at the Hans Bredow Institute for Media Research together with my colleague Jan-Hinrik Schmidt from the end of 2011 to mid-2014. The aim was to use a variety of methods to investigate how professional, editorially organised journalism integrates participatory elements into its content and which expectations and expectations (e.g. expectations that journalists have about the expectations of their audience) play a role on the part of journalists and the audience. The focus was on the question of how journalistic-professional orientation and audience participation interact with each other (Loosen/Schmidt 2012). To this end, we conducted a total of four case studies in journalistic editorial offices, covering three dimensions of contrast:

1. TV versus print newsrooms/offers including their corresponding online counterparts;

2. news-orientated versus entertainment-orientated journalism;

3. weekly versus daily publication frequency.

For both journalistic providers and audiences, participatory services (e.g. in the form of participatory offers made by an editorial office to its audience) and expectations of forms of audience participation and journalism were surveyed in order to be able to determine the respective extent of audience integration (i.e. the relationship between supply and demand of forms of audience participation) as well as the extent to which the respective expectations on the journalism and audience side match. Here I would like to highlight two results that can illustrate the kind of findings that can be obtained with such a question and a research design that takes both the journalism and the audience side into account. These are the results of the Süddeutsche Zeitung case study, which are based on surveys of SZ journalists and users of sueddeutsche.de (Heise et al. 2014).

A central question concerns the comparison of journalistic self-image and external image: On the one hand, we asked SZ journalists in an editorial survey what their profession is about and, on the other hand, members of the public which tasks they believe journalists who work for the Süddeutsche Zeitung should primarily fulfil. A total of 19 items were specified, which were to be rated on a scale from 1 ("strongly disagree") to 5 ("strongly agree"). Table 1 documents the results: The mean values for the individual items are shown for the journalism and audience sides; they are sorted in ascending order according to the size of the difference in the mean values between the two groups.

It is clear that the comparison of the journalistic role self-image and the external role image that the surveyed users have of Süddeutsche Zeitung journalists shows a very high level of agreement: 14 of the 19 items surveyed show a mean difference of less than 0.5 scale points. The highest difference is 0.65 (item 19 = "concentrate on news that is of interest to the widest possible audience") and is therefore still well below one scale point. However, even if the differences in self-image and external image are quite small overall, there are seven highly significant differences between the two groups (see Table 1, items 13 to 19 - marked with ***).

In four of these cases, the journalists consider something to be more of a part of their professional task than it is or should be in the eyes of their audience (positive mean difference); in the remaining three cases (negative mean difference), it is the other way round.

Tab. 1: Case study Süddeutsche Zeitung: Congruence of journalistic self-image and external image

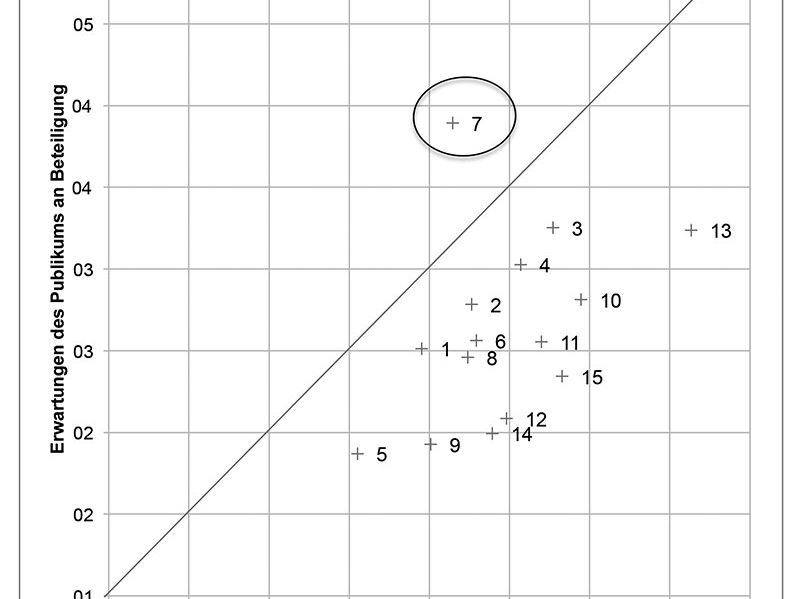

The extent of congruence between journalistic self-image and external image can also be visualised - then it is easy to see at a glance in which points the assessments of journalists and audience members are close together or differ (see Fig. 1): Points that lie on the diagonal line represent items that are assessed similarly on both sides; if they lie at the top right, the respective journalistic tasks tend to be agreed with, if they lie at the bottom left, this tends not to be the case. It can therefore be seen that the three most important tasks that SZ journalists name for themselves are of a classic journalistic nature: explaining and communicating complex facts (item 10), criticising grievances (item 8) and informing the audience as neutrally and precisely as possible (item 11). And these are precisely the three most important journalistic tasks in the eyes of their audience. Both sides were similarly in agreement, albeit negative, on the item "enabling users/readers to maintain social relationships with each other" (item 2): This (potential) task is clearly the most strongly rejected by the audience members surveyed. The SZ journalists reject it to roughly the same extent as the (potential) task of creating opportunities to publish user-generated content (item 15); although this is rejected less strongly by the audience members, it is still clearly rejected.

With regard to four journalistic tasks, it is comparatively clear that journalists - more so than the audience members surveyed (items to the right of the diagonal line) - see it as their task to concentrate on news that is of interest to the widest possible audience (item 19), to offer the audience entertainment and relaxation (item 18), to provide the audience with something to talk about (item 16), to offer help in life and to serve as a source of advice (item 14). Conversely, the audience expects SZ journalists to monitor politics, the economy and society (item 17) even more than journalists themselves consider this to be part of their job (items to the left of the diagonal line).

We also have corresponding data for the importance (assumed by editors) that participatory offerings have for the SZ audience (see Table 2 and Fig. 2). Here, the audience was asked how important they considered various forms of audience participation to be. This data was contrasted with the assessments of journalists, who were asked how important they considered these forms of audience participation to be for their readers/users.

Tab. 2: Congruence of (expectation) expectations of inclusion offerings of the Süddeutsche Zeitung

The items are sorted according to the size of the MW difference D. The scales ranged from 1 ("completely unimportant") to 5 ("very important"). The scale in the public questionnaire was subsequently reversed. "Don't know / can't say" was not taken into account when calculating the mean value. Marked mean differences are significant with * p<.05, ** p<.01, *** p<.001.

Even the first visual impression of Figure 2 makes it clear that journalists overestimate their audience's expectations of participation opportunities: They assume that their audience has a stronger desire to participate with regard to almost all the participation- or transparency-oriented services surveyed than the users themselves indicate (= positive mean difference and a position of the data points to the right below the diagonal). The difference is almost without exception over 0.5 and in many cases over one scale point, which corresponds to a comparatively high difference.

The only exception here is an aspect relating to source transparency: the audience members surveyed expect to receive significantly more additional information and references to the sources of a story (item 7) than the journalists surveyed assume: This is the only item with a negative mean difference, indicating that the SZ journalists surveyed underestimate this expectation of their audience. This is a finding that we also found in our other three case studies (Tagesschau, ARD-Polittalk, Der Freitag). For the other items, the difference in (expectation) expectations is particularly pronounced with regard to the editorial team's presence on network platforms (item 12), the public demonstration of its connection to the Süddeutsche Zeitung (item 14) and the opportunity to discuss Süddeutsche Zeitung topics (item 15). The journalists surveyed also believe that the most important thing for their users is to be taken seriously (item 13). For the members of the public, on the other hand, this is the most agreeable item - after source transparency and on a par with the expectation of being able to forward content quickly and easily (item 3) - but on average it is only slightly above the centre of the scale.

What next? Transforming communications and communicative figurations

With the spread of the Internet and social media, forms of audience participation in professional journalism are becoming increasingly diverse - and we can assume that these expanded forms of communication will continue to change the relationship between journalism and (its) audience, lead to work processes that are coordinated with them - and also influence the creation of journalistic statements. This is the reason why I would like to push ahead with this topic as part of the "Communicative Figurations" research network of the Universities of Bremen and Hamburg and the Hans Bredow Institute for Media Research.

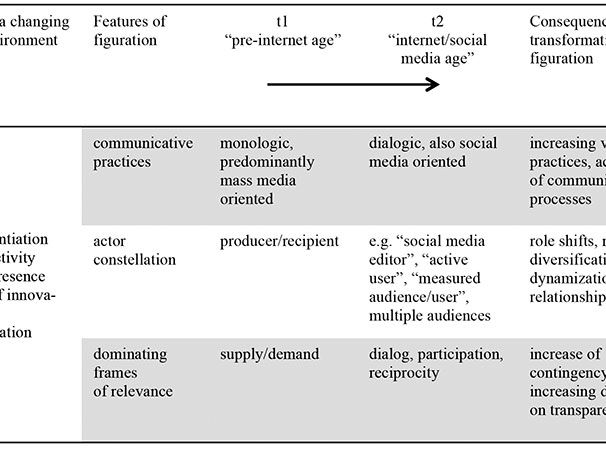

In this research network, we start with the initial observation that the changes in our media environment can be described with the help of at least five trends (see Table 3): The increasing differentiation, connectivity and omnipresence of/by media, the high pace of innovation and datafication, which is caused, among other things, by the digital traces we leave behind in all our usage activities on the Internet and which entail new forms of audience observation and measurement for journalism, for example.

Against this background, we are now focussing on very different phenomena and research questions in various research projects as part of our research network, but we are all investigating them with the help of the concept of communicative figurations (Hepp/Hasebrink 2014). In the context of my project, this means modelling the journalism/audience relationship as a communicative figuration and describing it along certain communicative practices, the actor constellation and its thematic framings or dominating frames of relevance.

With this tool, we can - if we very roughly define a point in time t1 as the "pre-internet age" and compare this with t2, the "internet/social media age" - visualise very well how the journalism/audience relationship is changing or at least expanding from mass to social media conditions. This change or expansion has consequences for all elements of the communicative figuration of the journalism/audience relationship: the communicative practices are expanding from monological and oriented towards the conditions of mass media towards dialogue and oriented towards the conditions of social media; this includes an expanded media ensemble and more diverse forms of communication between journalism and the audience as well as an acceleration of communication processes. And the classic actor constellation of sender/receiver is also becoming more dynamic and differentiated, with both journalists in their professional role and the audience having an expanded repertoire of possibilities at their disposal. The audience can become an active user and thus become active in a similar way to a journalist. Editorial departments are increasingly employing so-called social media or community editors who, among other things, take care of feedback and other contributions from the audience. In addition, different forms, intensities, observations and measurements of audience activities on different channels and platforms are leading to a differentiation of the audience image of journalists, who now perceive their audience less as one size, but rather differentiate it into multiple audiences according to various attributes and participation channels (e.g. active vs. passive, print readers vs. online readers, Facebook commenters vs. letter writers). For the thematic framing, the sense orientation of the journalism/audience relationship, this can ultimately mean that the classic orientation of supply and demand is expanded in the direction of dialogue, participation and reciprocity/reciprocity. Possible consequences on the audience side can be seen in increased demands for transparency (of journalistic work processes) and in an increase in and the normalisation of contingency experiences that arise, for example, from conflicting or increasingly diverse descriptions of reality by journalism and audience members.

Conclusion

Journalism is under great pressure to transform - the redefinition of its audience relationship is a central factor here. However, this transformation is neither linear nor uniform for all areas of journalism: it is different for traditional brands such as the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung than for start-ups such as Krautreporter or piqd, as well as for individual journalists and audience members. Nevertheless, the relationship between journalistic performance roles and audience roles is becoming more dynamic and less distinct. At its core, however, journalism still means the production of communication offers - users have the power to accept them or not.

This raises a central question: What relationship between proximity and distance in the relationship between journalism and the audience can we consider functional for journalism? Do more intensive contact and more knowledge about the audience also lead to better journalism?

The communication conditions changed by the internet and social media have broken the gatekeeper monopoly of journalism - they potentially allow everyone to publish their own constructions of reality and to comment on others, thus visualising the constructed nature of media reality(ies). In this way, experiences of contingency are also increasing; they are being made everyday, as it were, because digital media environments in particular sensitise us to the contingency of media constructions of reality and make them visible: Everything could also be selected differently and differently, reported and said differently. And this is precisely what is negotiated in social media and comment forums, among other places. This can be observed, for example, during major events (such as the crash of Germanwings flight 9525), where journalistic reporting on social media is accompanied by instant media criticism. Here, everything happens at the same time: an event, the reporting, the criticism of the reporting, the criticism of the criticism of the reporting. The question of the how of media constructions thus becomes a question that permanently accompanies social discourse.

Further reading

Boczkowski, Pablo J./Mitchelstein, Eugenia (ed. ) (2013): The news gap. When the information preferences of the media and the public diverge. Cambridge, Mass.

Frank, Arno (ed.) (2013): A mob with an opinion. On the stupidity of the swarm. Zurich.

Glotz, Peter/Langenbucher, Wolfgang R. (eds.) (1993, first published in 1969): Der missachtete Leser. A Critique of the German Press. Munich.

Heise, Nele/Reimer, Julius/Loosen, Wiebke/Schmid, Jan-Hinrik/Heller, Christina/Quader, Anne (eds.) (2014): Audience inclusion at the Süddeutsche Zeitung. Case study report from the DFG project "Die (Wieder-)Entdeckung des Publikums". Hamburg (= Working Papers of the Hans Bredow Institute 31).

Hepp, Andreas/Hasebrink, Uwe (2014): Human interaction and communicative figurations: The transformation of mediatised cultures and societies. In: Lundby, Knut (ed.): Mediatisation of Communication. Berlin et al, pp. 249-272.

Loosen, Wiebke (2013): Audience participation in journalism. In: Meier, Klaus/Neuberger, Christoph (eds.): Journalism Research. Status and perspectives. Baden-Baden, pp. 147-163.

Loosen, Wiebke/Schmidt, Jan-Hinrik (2012): (Re-)Discovering the Audience. The Relationship between Journalism and Audience in Networked Digital Media. In: Information, Communication & Society, Special Issue "Three Tensions Shaping Creative Industries in a Digitised and Participatory Media Era" (Ed. Oscar Westlund) Vol. 15, No. 6, pp. 867-887.

Loosen, Wiebke/Schmidt, Jan-Hinrik/Heise, Nele/Reimer, Julius (eds.) (2013a): Audience inclusion in an ARD political talk programme. Summarising case study report from the DFG project "Die (Wieder-)Entdeckung des Publikums". Hamburg (= Working Papers of the Hans Bredow Institute No. 28).

Loosen, Wiebke/Schmidt, Jan-Hinrik/Heise, Nele/Reimer, Julius/Scheler, Mareike (eds.) (2013b): Audience inclusion in the Tagesschau. Case study report from the DFG project "Die (Wieder-)Entdeckung des Publikums". Hamburg (= Working Papers of the Hans Bredow Institute 26).

Loosen, Wiebke/Dohle, Marco (eds.) (2014): Journalism and (its) audience. Interfaces between journalism research and reception and impact research. Wiesbaden.

Meyen, Michael/Riesmeyer, Claudia (eds.) (2009): Dictatorship of the audience. Journalists in Germany. Constance.

Reimer, Julius/Heise, Nele/Loosen, Wiebke/Schmidt, Jan-Hinrik/Klein, Jonas/Attrodt, Ariane/Quader, Anne (eds.) (2015): Audience Inclusion at Friday. Summarising case study report from the DFG project "Die (Wieder-)Entdeckung des Publikums". Hamburg (= Working Papers of the Hans Bredow Institute 36).

Scholl, Armin/Weischenberg, Siegfried (ed.) (1998): Journalism in Society. Theory, Methodology and Empiricism. Wiesbaden.

Wolf, Fritz (ed.) (2015): "We are the audience!" Loss of authority of the media and compulsion to dialogue. Frankfurt a. M. (= Otto Brenner Foundation Workbook 84).