Towards a European minimum wage – different forms of networking among unions and employers’ organisations in the EU

Author: Ilana Nussbaum Bitran

The Employment and Social Affairs Committee of the EU has recently agreed on a joint position concerning a “fair minimum wage”. After two phases of consultation in 2020, the European Commission already developed a Directive proposal which “aims to ensure that the workers in the Union are protected by adequate minimum wages allowing for a decent living wherever they work”. The idea is to develop and put into force a European legal instrument ensuring that every worker in the European Union receives a fair minimum wage, which should be set following national traditions being these collective agreements or by statutory legal provisions. Given the differences in industrial relation systems in the European member states, the proposed directive encountered both opposition and support. On the one hand the Scandinavian countries, where minimum wages are set through collective agreements respecting the peculiarities of each sector, put up resistance against the proposed policy arguing that it will disturb national industrial relation traditions and could also eliminate differences between sectors. On the other hand, countries such as France, Spain or Portugal already have statutory minimum wages. In these countries, a coordination of EU minimum wages could be much simpler than in the first group of countries. After an intense discussion, on December 6th 2021, the EU labour ministers agreed on introducing minimum standards with two votes (Denmark and Hungary) against the regulation and two abstentions (Austria and Germany). In the last minute, Sweden decided to back the draft law, showing how member states are open to change their mind in order to find joint positions.

Given this scenario, we would like to understand how the cooperation between national and transnational organisations of the social partners is clustered in order to find joint positions concerning a European minimum wage. In other words, how different actors such as trade unions and employers’ organisations in different levels (national and transnational) find common positions concerning a more or less binding directive or proposal for a European minimum wage. Using a standardized questionnaire, which was sent to 102 trade unions and 121 employers organisations in 20 member states and to organisations at the EU transnational level, we wanted to map a network of actors. The main question to be answered was “Please list up to five of the most important organisations in your country and the rest of Europe with which your organisation is or has been in contact in relation to the EU Minimum Wage Directive”. We focused on three sectors: road transport, construction and cleaning as sectors where minimum wage regulations have a high relevance due to the generally low wage level. We received 33 responses from trade unions and 24 from employers’ associations, which represent a response rate of 25,5% from the total of organizations. Even though this number seems to be small, it is in line with the response rate of similar researches[1]. With the received responses we conducted a network analysis to study the position and connexions of national trade unions as well as employers’ organizations in relation to the European minimum wage directive.

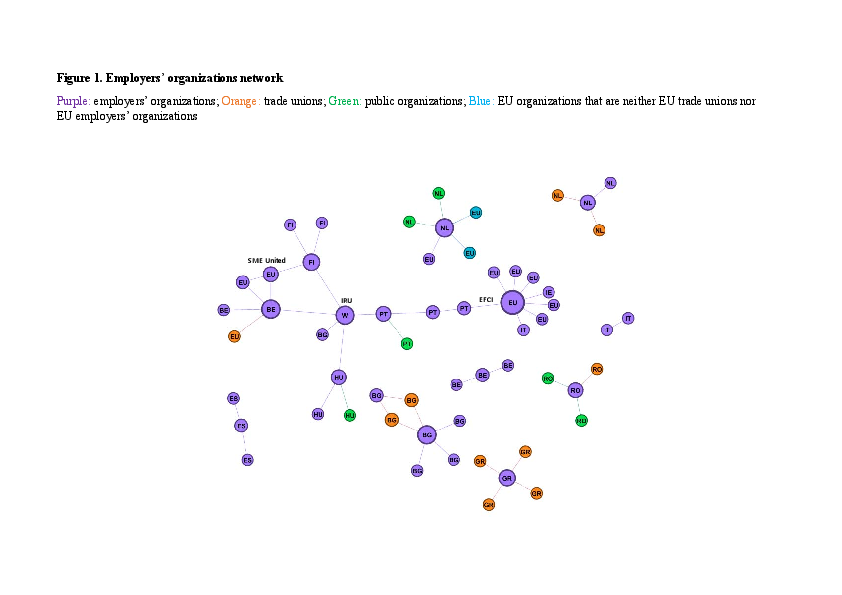

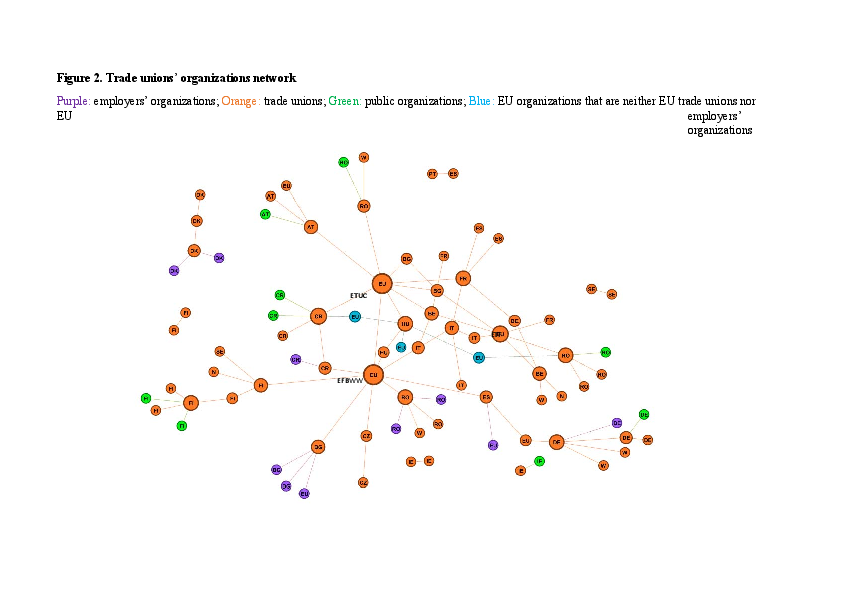

As we can see in the networks (Figure 1 and 2), the interactions between trade unions as well as between employers’ associations within industrial sectors happen in two different levels. On the one hand at the national level where concrete demands can be shaped and turned into national labour law or the country’s position on the European level, and, on the other hand at the European level where different (trans-)national actors may facilitate or hinder the development and put into practise of the new EU Directive. On the national level the connections tend to be denser and they usually have one central actor, who in turn, connects the national subnetwork with the European level. In comparison with the employers’ network, the trade unions’ network is much denser. We can see much more connections both within countries as well as on the European level. This may have ‘technical’ reasons as we got more answers from trade unions compared to employers’ associations. Another reason may be the need of collective organisations as well as the ideas of international solidarity to influence policies that has been constantly present in the history of workers’ movements. In the employers’ network, the number of “islands” – organizations that are connected between them but disconnected from the main network – is much bigger. These islands tend to stay at the national level, connecting only employer’s associations from one country. This network formation may be related with the importance of national connections for employers when discussing issues linked with the minimum wage, showing that the EU level may play a secondary role when it comes to discuss wage-related issues. Overall we can see that in both networks, transnational EU organizations such as the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) or the European Cleaning and Facility Service Industry (EFCI) are present to connect different country organizations and they also work as bridges with other EU organizations.

In order to answer a second question, namely, what are the motivations behind the development of transnational demands and positions regarding a European minimum wage, we are conducting expert interviews with EU transnational organizations, which have shown to be the most central actors of our networks. We would like to understand in more detail the national and transnational connections and information flow within the three sectors. Focusing on sector specific interests we may explore whether a common understanding of the problem of low wages in the respective sectors helps to generate common positions at the transnational level or whether competition for labour may favour positions on different national wage regulation.

This is still work in progress and the analysis of the interviews will take some time, but we are already planning a scientific journal article regarding the transnational position taking and motives behind the European minimum wage. If you want to know more about this issue, do not hesitate to contact us or visit this blog again, we will keep you posted!

[1] Dür & Mateo 2014 (p. 591) point out that for business interest researches “comparable studies report response rates ranging from 19.0 percent for a survey carried out in 2012 (Kohler-Koch et al., 2013), to 40.9 percent for a similar study in the 1990s (Eising, 2009), and to 44.9 percent for a survey of Danish interest groups (Binderkrantz and Krøyer, 2012).” Also Larsson & Törnberg 2019 got a response rate of 37% while surveying only trade unions in the EU.