Laboratory for Molecular Diabetology

Questions on Molecular Diabetology Research

Why does diabetes develop? Why does the β-cell die and how can we prevent this? This is what researchers at the Laboratory of Molecular Diabetology at the University of Bremen are investigating. Diabetes mellitus affects more than 430 million people worldwide; the number of sufferers will continue to rise each year unless urgent measures are taken to combat the disease. Patients with diabetes are particularly affected by the current COVID-19 pandemic; the viral disease not only has a more severe course, but also affects chronic diabetic metabolism in the body. Diabetes is caused by decreased insulin secretion and death of β-cells in the pancreas. Both autoimmune type 1 diabetes, which occurs in childhood, and type 2 diabetes, which is caused by obesity and physical inactivity, develop because of the loss of insulin-secreting β-cells. A new and promising strategy in the causal treatment of diabetes is to promote the survival of the β-cell, as currently available treatments for diabetes only serve to alleviate symptoms and do not address the causes of the disease itself.

Using chemically novel drugs or modified RNAs with high cell specificity, lower potential for side effects, and readily controllable modes of action, scientists: can turn off proteins that directly trigger the loss of insulin-producing β-cells and thus prevent the development of diabetes. This is the goal of their work.

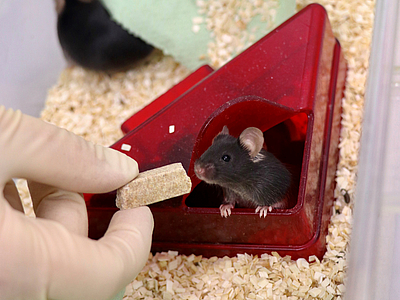

The researchers are using mice that develop diabetes, the mechanisms of which are similar to the disease in humans and are associated with a loss of survival and function of the β-cells. A preclinical study requires animals treated with placebo and animals treated with the drugs. The various drug effects must be closely examined and monitored during the study. The researchers conduct trials exclusively within animal studies approved by the Senatorial Office. The major organs are harvested and these are also used for teaching in the laboratory after the study is completed. Here, students are able to study the functions and morphology of the organs very well, and in doing so, they contribute to the development of new therapies against diabetes.

There are many very good alternative methods. Before the scientists conduct their studies in animal experiments, the concepts are tested in cell experiments. For this purpose, they have various β-cell lines, i.e. β-cell-like cells, at their disposal, in which they analyze precisely the mechanisms of β-cell loss and diabetes development in cell culture. In doing so, they stimulate the cells with high sugar and fatty acid concentrations, exactly what also triggers type 2 diabetes. Or they work with certain viruses and inflammatory messenger substances that are involved in the development of type 1 diabetes. In these experiments, they use genetic analyses to find which cellular signaling pathways trigger the disruption of the β-cell. First, they test the appropriate drugs that target this disruption and then investigate whether this is exactly what is present in human diabetes. To do this, they obtain cells from organ donors who have given their consent for scientists to use these cells in research. These experiments with human cells have been carefully reviewed and approved by an ethics committee beforehand.

Several years of intensive research pass before the projects are tested on animals. But how and whether such a drug really works in an intact whole organism can only be tested in animal experiments, since complex physiological and pathophysiological metabolic processes are involved. All preceding cell experiments lead to the fact that the number of animals can be kept as low as possible.

If the effect in mice can be confirmed, clinical trials will follow. But this is a long road. It is particularly important then if studies from the cell and animal experiments have already been confirmed individually in the clinic. As an example, a patient with severe diabetes and high sugar levels over many years was able to achieve complete normalization of her blood sugar with the newly developed drug. Scientists hope that this success in the treatment of diabetes can be confirmed in larger clinical studies and that their investigations can help many people in the future.

![[Translate to English:] Mäusehaltung Mouse in plastic cage](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/b/csm_Maeusehaltung1_Copyright-Universitaet-Bremen_8e06b92265.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] Mäusehaltung Mouse husbandry](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/1/csm_Maeusehaltung_2_545dcda002.jpg)